Don Loke, Connecticut, Aug 2025 — Independent in Time

I arrived into Goldens Bridge in New York State around 9 a.m., having left Grand Central Station in NYC. I was picked up from the commuter train by Don Loke. I have known Don for almost thirty years at this point. He used to visit my store in Redwood City, California, as an importer for a variety of high-end Swiss brands — Audemars Piguet, Breguet, Daniel Roth, Parmigiani, and others.

Don always struck me as a straightforward guy — someone willing to help retailers with whatever they needed, and someone who clearly knew what he was talking about when it came to fine watchmaking and horology in general. When I first met him, my knowledge level wasn’t yet developed enough to appreciate his abilities as a watchmaker.

Years later, that changed. I had a 1920s Vacheron Constantin pocket watch with a guilloché silver dial that had badly discolored over the years — likely from moisture intrusion. I asked a mutual friend, who was running Vacheron Constantin for the Americas at the time, who might be best to restore it. Without hesitation, he said, “Send it to Don Loke.”

So I did. Six weeks later, the watch came back looking remarkably improved — not perfect, but carefully restored in a way I hadn’t thought possible. And, true to Don’s nature, he hadn’t charged nearly enough for the work.

Don was there to pick me up with a smile. We headed about twenty minutes east into Connecticut to his home workshop and atelier. I’d been speaking with Don for over two years about an incredible project he’s been developing for many years — something that, to my knowledge, no one has ever achieved in watchmaking before. The fact that an American watchmaker is doing it makes it all the more intriguing.

As is often the case with significant new developments in the horology field, there’s a financial component that must be met before the first prototype can be completed. How to proceed in the production of the caliber in a fiscally sensible way? Is it a tiny series, essentially funded by early adopters in the “Subscription model” often seen, or is it to develop and make a small series of say 50-100 movements that are completed and ready for sale with out enthusiasts/collectors putting up any money/deposits and waiting? This is where Don is at. He has seen both methods and wants to get this right for all parties involved. There is also the aspect of where the majority of the serially made parts will come from. Will it be USA only based manufacturing or will he rely on relationships forged over decades in Switzerland, for sourcing? To be determined at the time of writing…

Don had previously sent me CAD renderings of the watch as well as a photo of a 4X scale model of his patented D. Loke “Double Spring Détente Escapement”™, a double-wheel chronometer escapement. At the same time, he’s also designed a more traditional Swiss lever, manual-wind, time-only watch. It features a silver guilloché dial, a rose gold case, and a sub-seconds hand at six — elegant, traditional, and a joy to see emerging from an American watchmaker of Don’s capability and reputation.

Don is the kind of watchmaker that collectors and retailers turn to when they’ve exhausted every other option. When a century-old timepiece baffles everyone else, Don can recreate the missing part himself — because he not only has the knowledge but also the machines and tools needed to manufacture every component of traditional horology.

When we arrived at his home, the first stop was his workbench — a beautiful wooden bench made by an Amish craftsman. Don had purchased it from one of his mentors, paying it off slowly over several months in hundred-dollar installments. On it lay the familiar tools of a master watchmaker.

Don Loke’s handmade Amish workbench, laid out with the tools of his craft.

Under a glass dome sat an elegant and highly complex pocket watch caliber. Don lifted the dome and handed me the movement, asking what I thought of it. The piece was strikingly three-dimensional — and when he turned it over, revealing the dial side, I realized I was looking at something extraordinary: a triple chronograph, probably made between 1900 and 1910, with three central seconds hands in blue, purple, and polished steel.

Don revealing the triple-chronograph movement, c.1900–1910, under a glass dome.

This watch had arrived to him in pieces, after others had failed to reassemble it. Don restored, refinished, and rebuilt it so it now ran as it was originally designed.

Detail of the triple-chronograph mechanism showing three column wheels and intricate gearing.

The lovely enamel dial and three seconds hands!

These are the kinds of projects Don has quietly worked on — often under the radar — for over forty years. Like many highly skilled craftsmen, his self-promotion is far less prominent than his extraordinary watchmaking ability.

Another fascinating piece on his bench that day was a Patek Philippe Calatrava Ref. 2526, recognizable by its ivory enamel dial and the automatic caliber 12-600 with its guilloché 18k yellow gold rotor.

Patek Philippe Calatrava Ref. 2526 with enamel dial and guilloché gold rotor.

Can you imagine Patek Philippe applying hand guilloché on their standard automatic calibers today?

There is something ineffably beautiful about an enamel dial in a wristwatch. The Patek had been sent to Don for routine service. This example, cased in rose gold, is quite rare, as most were made in yellow gold.

While my horological understanding doesn’t match Don’s, I can certainly recognize genius when I see it — and his Double Spring Détente Escapement is, to my knowledge, unprecedented. When Don shared the idea with the late George Daniels, Daniels reportedly smiled and said, “Why not? Nobody’s done that yet in a wristwatch.”

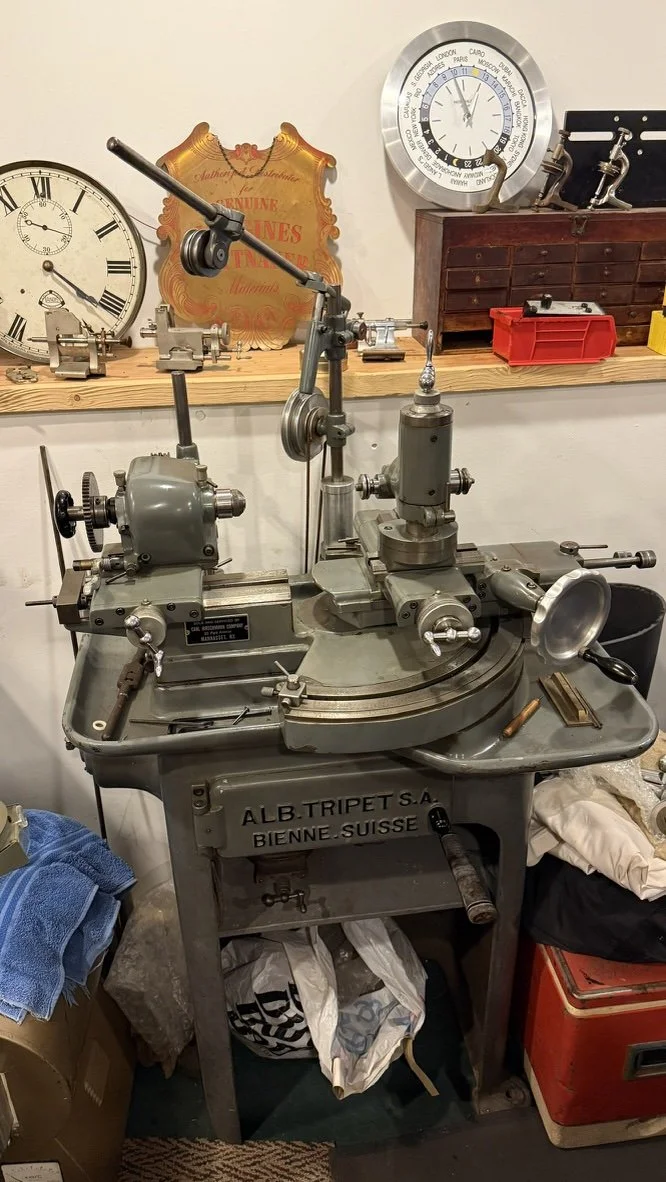

We then headed downstairs to what I term the garden garage — a workspace filled with traditional watchmaking machinery he’s collected over his career. It’s one of the most complete private workshops I’ve ever seen, full of older, often historic machines I’d never encountered before.

The “garden garage” workshop, filled with traditional machinery for making and restoring watches.

A Hauser milling machine occupied one corner, complete with its optical viewing scopes that ensure each component is precisely machined.

Hauser precision mill with optical scopes for ultra-fine machining.

This is the workshop that allows Don to restore, repair, and rejuvenate nearly any traditionally made mechanical watch or pocket watch. Alongside the Hauser mill were his Schaublin 102 and Schaublin 70 lathes — instruments capable of precision down to one micron, enabling Don to craft parts to exact tolerances.

Schaublin 70 lathe set up for cutting a wheel with indexing attachment.

On one shelf sat two remarkably old machines used for making fusée cones — components found within early chain-and-fusée pocket watches. I’d never seen these before in any other workshop.

Don holding an antique fusée-cone cutting tool, used in 19th-century pocket watches.

Close-up of a fusée cone during machining

Nearby was a cam-driven pinion-making machine — sadly not running during my visit. When operating, these machines produce a rhythmic “click-clack” sound that’s both mechanical and musical.

Cam-driven pinion-making machine used for gear production in traditional horology.]

Don also owns several topping tool machines, used for cutting wheel teeth, as well as numerous specialized finishing tools — all essential for recreating components from watches that can be 100, 150, or even 200 years old.

Hand-operated Geneva striping machine for decorating bridges and plates.

Pinion polishing machine used for fine surface finishing

Don proudly standing among his array of traditional watchmaking machines.

Schaublin 102 lathe with full chuck set, showing clear signs of long professional use.

Tripet grinding machine, used for toolmaking and precision shaping

Milling machine used for bridge and plate fabrication.

We returned inside the house and descended again, this time into a windowless basement room filled with even more fascinating equipment for high-end artisanal watchmaking, prototyping, and restoration.

Small precision Levin lathe, used for miniature components.

High-speed micro-mill for precision machining

Among the equipment, Don showed me a clock he made while at Bowman Technical School in 1983 — a beautifully executed pendulum clock.

For some reason, I hadn’t expected to find both a Rose Engine and a Straight-Line Engine for guilloché work — but of course, Don has them. To be a complete watchmaker in the George Daniels tradition, one must also master decorative techniques.

Don’s finishing bench with guilloché engines and test plates for component fitting

Close-up of the Rose Engine for circular guilloché patterns

Straight-Line Engine used for linear guilloché decoration

Mounted above one workbench was a photograph of a young Don Loke with George Daniels, likely from the 1980s. Above it hung his WOSTEP certificate, earned in Biel, Switzerland in 1984 after completing an advanced course in Swiss horology.

Don Loke meeting George Daniels, circa 1980s

WOSTEP graduation certificate from 1984, Biel, Switzerland

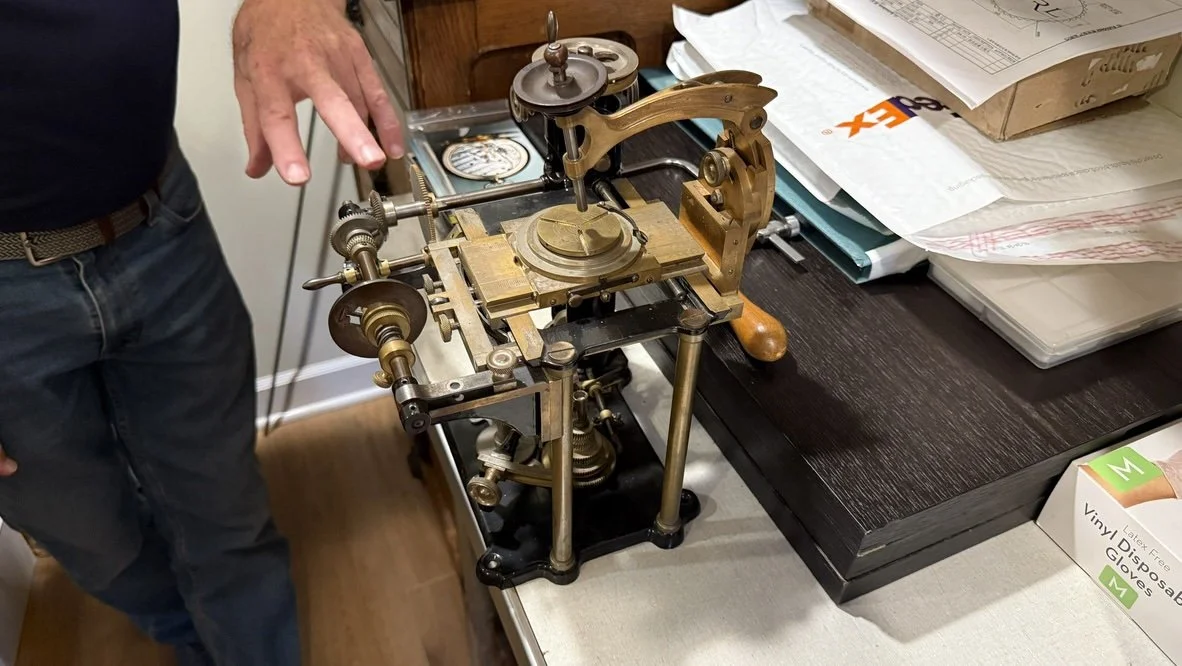

He then showed me a curious mystery machine he’d purchased without knowing its purpose. Don suspects it’s used for damascening — the decorative surface finishing once seen on vintage American pocket watch bridges — though he’s still figuring out exactly how it operates.

The mysterious damascening machine awaiting identification and restoration

Back upstairs in his main atelier, we turned our attention to the Double Spring Détente Escapement project. Don brought out the large 4X brass model of the escapement — and it’s a sight to behold.

Brass 4X model of Don Loke’s patented Double Spring Détente Escapement

The model demonstrates an ingenious mechanism: two “batwing” cams that lock and release the escape wheel, aided by a heart-shaped spring Don designed specifically for this purpose.

Close-up of the heart-shaped spring designed for the Double Spring Détente Escapement model

Don has designed not only this escapement but also a traditional lever escapement caliber. He’s made numerous prototype parts — jewels, escape wheels, and balance assemblies — though production has yet to begin due to his commitments to restoration work (and, as always, the financial realities of launching such a complex independent project).

Prototype escapement components, including escape wheels, jewels, and balance assemblies

He showed me the raw brass main plates and bridges of the lever-caliber design, still unfinished but beautifully proportioned.

Brass mainplate and bridges for the prototype Swiss lever caliber

Brass mainplatte for the Double Spring Detente Escapement caliber

Don was wearing what I’d consider his “entry-level” watch — a design he created around fifteen years ago. It’s an elegant automatic chronograph with an internal rotating timing bezel operated by a crown at 9 o’clock. The watch features two subdials for twelve-hour and thirty-minute counters and displays Don’s signature attention to detail.

The baton markers on the dial are particularly ingenious: at nine and three o’clock, they appear as half of their full shape, so when the minute hand aligns with a marker, its tip mirrors the baton perfectly. This allows for precise time reading and reflects Don’s obsession with functional beauty — a practical yet refined innovation I haven’t seen elsewhere.

Don Loke’s “Dress Chronograph” in titanium, featuring the internal rotating bezel and twin subdials.

He calls it simply the “Dress Chronograph.” The case is made from titanium, and inside beats a chronometer-rated Concepto 7750-derived caliber that Don reworks and finishes to his own standards.

The dial on his personal watch is a mesmerizing blue — shifting hue in different light. Another version features a white lacquer enamel dial (not fired in the kiln like a Grand Feu, but applied in multiple coats), with blue subdials and blue steel baton markers. Don showed me a loose dial from this variant, which was elegant and distinctive, with concealed pushers for chronograph operation.

Blue lacquer dial of Don’s titanium Dress Chronograph, shifting tone in natural light.

White lacquer dial variant with blue steel hands option.

Don’s personal watch from the movement side.

Over lunch, Don and I spoke about the business aspects of how we could help one another and reminisced about our thirty-plus years in the industry. We also discussed his escapement project — an ambitious step forward in horology.

The next crucial phase will be funding, enabling Don to produce a small series of watches rather than making them one by one. Crafting them individually might sound romantic, but it’s not practical or cost-effective for collectors — nor sustainable for an independent watchmaker of his caliber.

This is the reality of artisanal independent horology: balancing artistry and livelihood. Can a single craftsman build pieces worthy of the price that reflects the time, effort, and mastery invested? Will collectors recognize and support such groundbreaking work?

I believe so. What Don is doing is not just technically impressive — it’s historically important. His Double Spring Détente Escapement represents a new chapter in the long story of precision timekeeping, created not in Switzerland, but right here in the United States, by a true master of the craft.

Many thanks to Don Loke for his generosity, his time, and his willingness to open his world to me — from the train station at Goldens Bridge to the heart of his workshop. It was a morning filled with craftsmanship, innovation, and friendship.

Hungry smiles after a morning of serious horology!

He even drove me across Connecticut afterward to visit another American independent watchmaker — the next stop in my continuing exploration of the art of horology in the United States.